1 Week 1 Lecture

1.1 Week 1 Readings

For this week, I suggest Aho Chapter 2, and Sections 4.1, 4.2, 4.3.1, 4.3.2, 4.3.3, 4.3.4, 4.3.7, and 4.5. Logan Chapter 1 will help you get started in R if you are not already familiar with it.

I also recommend reviewing the Algebra Rules sheet.

1.2 Basic Outline

First half: - R - bootstrap, jackknife, and other randomization techniques - hypothesis testing - probability distributions - the “classic tests” of statistics - graphical analysis of data

Second half:

- regression (incl. ANOVA, ANCOVA)

- model building

- model criticism

- non-linear regression

- multivariate regression

Class Structure

Lecture on Tuesday

“Lab”” on Thursday

Problem sets are posted on Wednesdays (feel free to remind me via Slack if I forget), and are due before lecture the following Tuesday. This deadline is very strict, no exceptions. Turn in what you have before 8:00 am on Tuesday, even if its not complete.

Communication

Use slack!

Come to (both) office hours

I have instituted a new participation component to Biometry’s grading, see syllabus.

1.3 Today’s Agenda

- Basic probability theory

- An overview of univariate distributions

- Calculating the expected value of a random variable

- A brief introduction to the Scientific Method

- Introduction to statistical inference

1.4 Basic Probability Theory

Let’s imagine that we have a bag with a mix of regular and peanut M&Ms. Each M&M has two traits: Color and Type.

\[ \sum_{all \: colors} P(color) = 1 \] \[ \sum_{all \: types} P(types) = ? \] Note that the probabilities have to sum to 1.0 and that the probabilities also have to be non-negative. It turns out these are the only two requirements for a “legal” probability function. (Here we have discrete categories and so the probabilities add to one through a straightforward summation. The distribution of probabilities across categories is called the probability mass function. If these were continuous probabilities, like the distribution describing the weight of each M&M, the distribution would be called a probability density function and we would have to integrate [the continuous version of a sum] over all possible weights. Either way, the sum [or integral] over all possible values of the variable has to equal 1.0.)

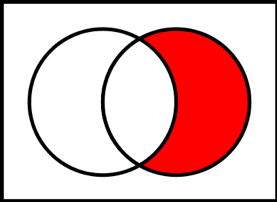

The complement (indicated by a superscript C) of a trait represents every object that does not have that trait, so the probability of the complement to Green is the probability of getting an M&M that is anything but green.

Figure 0.1: Red shading represents the complement. Source: Wikimedia Commons

\[ P(Green^c) = 1 - P(Green) \]

1.4.1 Intersection

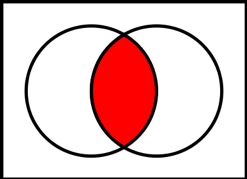

Figure 1.1: Red shading represents the intersection. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Now let’s pull one M&M out of the bag. If the color distribution of chocolate M&Ms and peanut M&Ms is the same, then these two traits are independent, and we can write the probability of being both Green and Peanut as

\[ P(Green \: AND \: Peanut) = P(Green \cap Peanut) = P(Green) \cdot P(Peanut) \]

This is called a Joint Probability and we usually write it as \(P(Green,Peanut)\). This only works if these two traits are independent of one another. If color and type were not independent of one another, we would have to calculate the joint probability differently, but in the vast majority of cases we are working with data that we assuming are independent of one another. In these cases, the joint probability is simply the product of all the individual probabilities.

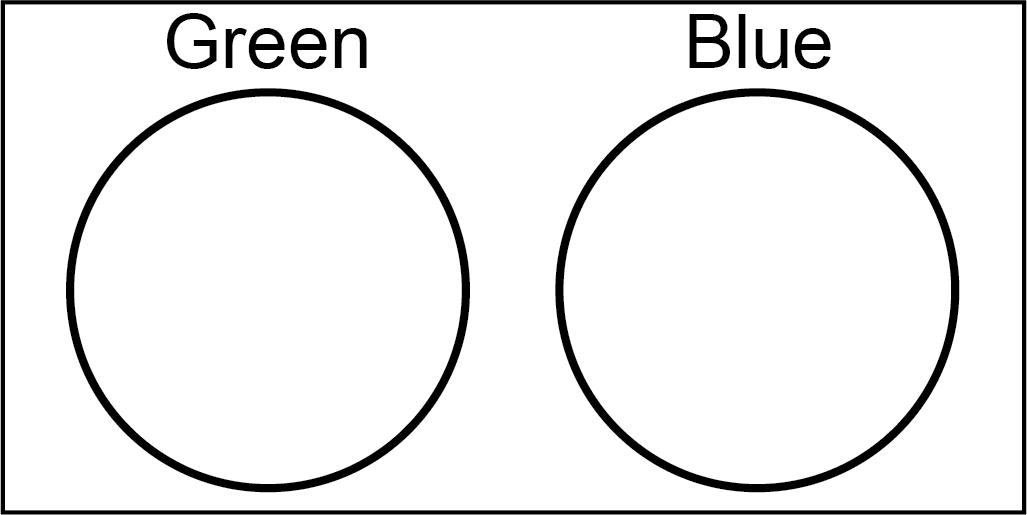

Note that

\[ P(Green \: AND \: Blue) = P(Green \cap Blue) = 0\] because an M&M cannot be Green and Blue at the same time. in this case,

Figure 1.2: In the case of two different colors, the intersection is empty.

1.4.2 Union

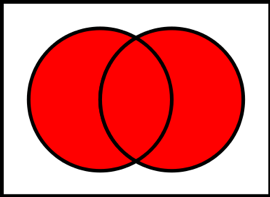

Figure 1.3: Red shading represents the union. Source: Wikimedia Commons

\[ \begin{align*} P(Green \: OR \: Peanut) &= P(Green \cup Peanut) \\ &= P(Green) + P(Peanut) - P(Green \cap Peanut) \end{align*} \]

Question: Why do we have to subtract off the intersection?

Click for Answer

If we do not subtract off the intersection, then the probability of Green AND Peanut will be double counted.1.5 Multiple events

Let’s consider what happens when we pull 2 M&Ms out of the bag

\[ P (Green \: AND \: THEN \: Blue) = P(Green) \cdot P(Blue) \]

Question: What if we didn’t care about the order?

Click for Answer

If we do not care about the order, then the combination of one Green M&M and one Blue M&M could have come about because we drew a Blue M&M and then a Green, or a Green and then a Blue. Because there are two ways to get this outcome (and they are mutually exclusive, so we can simply add the two probabilities), the total probability is simply 2 \(\times\) P(Green) \(\times\) P(Blue).1.6 Conditionals

Now we will introduce the ideal of a conditional probability.

\[ P(A \mid B) = P(A \: conditional \: on \: B) \] Let’s say we have a bivariate distribution (that just means we have two traits being discussed, similar to M&M color and M&M type above) for discrete quantities such as hair color and eye color (which we will use because they are intuitive but not independent traits), and we survey a number (n=20 in this case) of students.

| Brown | Blond | Red | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blue eyes | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Brown eyes | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Green eyes | 2 | 1 | 1 |

This table summarizes the joint distribution for hair color and eye color, which we would write as

\[ P(hair,eye) \]

Remember that for any two traits A and B that are independent,

\[ P(A,B) = P(A) \times P(B) \]

However, in this case, we don’t have any reason to believe that hair and eye color are independent traits. People with blue eyes have a different probability of having brown hair than people with brown eyes. These are called conditional probabilities. For example, the probability of having blue eyes conditional on having blond hair is given by 4/7. We write this as follows

\[ P(eyes=blue|hair=blond) \]

The | symbol represents the “conditional on” statement.

We might also be interested in the marginal probabilities, which are those probabilities representing hair color irrespective of eye color, or eye color irrespective of hair color. In the example given, the marginal probability of having blue eyes is 7/20. The marginal probability of having blond hair is also 7/20. These are univariate probabilities, and are written as

\[ P(eye) \]

or

\[ P(hair) \]

The relationship between joint, marginal, and conditional distributions can be seen in the following statement

\[ P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue},\mbox{hair}=\mbox{blond})=P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue}|\mbox{hair}=\mbox{blond})P(\mbox{hair}=\mbox{blond}) \]

We can see that this works out as it should

\[ \frac{4}{20}=\frac{4}{7} \times \frac{7}{20} \]

If we want to know the probability of having blue eyes (and didn’t care about hair color) than we would want to add up all the possibilities:

\[ P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue})=P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue}|\mbox{hair}=\mbox{blond})P(\mbox{hair}=\mbox{blond}) \\ +P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue}|\mbox{hair}=\mbox{brown})P(\mbox{hair}=\mbox{brown}) \\ +P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue}|\mbox{hair}=\mbox{red})P(\mbox{hair}=\mbox{red}) \] We can state this more simply as a sum:

\[ P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue})=\sum_{\mbox{all hair colors}}P(\mbox{eyes}=\mbox{blue}|\mbox{hair}=\square)P(\mbox{hair}=\square) \]

For continuous distributions, the same principles apply. Let’s say we have a continuous bivariate distribution \(p(A,B)\). The marginal distribution for A can be calculated by integrating over B (we call this “marginalizing out” or “marginalizing over” B)

\[ p(A=a)=\int_{b=-\infty}^{b=\infty}p(A=a|B=b)p(B=b)db = \int_{b=-\infty}^{b=\infty}p(A=a,B=b)db \]

Notice that, in all cases (discrete or continuous), the relationships among marginal, conditional, and joint distribution can written as

\[ p(A|B)\times p(B)=p(A,B) \] or as

\[ p(B|A)\times p(A)=p(A,B) \]

Therefore,

\[ p(A|B)=\frac{p(B|A)p(A)}{p(B)} = \frac{p(A,B)}{p(B)} \] Ta da! We’ve arrived at Bayes Theorem, using nothing more than some basic definitions of probability.

In Bayesian analyses (which we will not get into this semester), we are using this to calculate the probability of certain model parameters conditional on the data you have. But to find out more, you’ll have to take BEE 569.

\[ P(parameters \mid data) \cdot P(data) = P(data \mid parameters) \cdot P(parameters) \]

\[ P(parameters \mid data) = \frac{P(data \mid parameters) \cdot P(parameters)}{P(data)}\]

1.7 A few foundational ideas

There are a few statistics (a statistic is just something calculated from data) that we will need to know right at the beginning.

For illustration purposes, lets assume we have the following (sorted) series of data points: (1,3,3,4,7,8,13)

There are three statistics relating the “central tendency”: the mean (the average value; 5.57), the mode (the most common value; 3), and the median (the “middle” value; 4). We often denote the mean of a variable with a bar, as in \(\bar{x}\). There are also two statistics relating to how much variation there is in the data. The variance measures the average squared distance between each point and the mean. For reasons that we will discuss in lab, we estimate the variance using the following formula

\[ \mbox{variance}_{unbiased} = \frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_{i}-\bar{x})^{2} \] rather than the more intuitive

\[ \mbox{variance}_{biased} = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_{i}-\bar{x})^{2} \]

Why? It turns out that the unbiased estimator is not the sum of squared deviation per data point but rather the sum of squared deviation per degree of freedom. What’s a degree of freedom? Glad you asked…

1.8 Degrees of freedom

What is meant by “degrees of freedom”?

Draw five boxes on the board:

We want the mean to be 4 so the sum has to be 20. Let’s start filling in boxes…

Do we get to choose the last number? No! The last number is constrained by the fact that we already fixed the mean to be 4.

So we only have 4 degrees of freedom, the last box is prescribed by the mean. So if we know the mean of a sample of size n, we only have n-1 remaining degrees of freedom in the sample.

degrees of freedom (dof)=sample size (n)-number of parameters already estimated from the data (p)

If we go back for a second, it turns out that the real definition of the sample variance is

\[ \mbox{variance} = \frac{\mbox{sum of squares}}{\mbox{degree of freedom}} \]

What is the sum of squares?

\[ SS = \sum(Y-\bar{Y})^2 \] How many degrees of freedom did I start with? (n)

How many did I lose in the calculation of the SS? (1, for \(\bar{Y}\))

Therefore, an unbiased estimate of the population variance is:

\[ SS = \frac{\sum(Y-\bar{Y})^{2}}{n-1} \] ##Back to talking about variance and standard deviation

Keep in mind that variance measures a distance squared. So if your data represent heights in m, than the variance will have units \(m^{2}\) or square-meters.

The standard deviation is simply the square-root of variance, and is often denoted by the symbol \(\sigma\).

\[ \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n-1}\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_{i}-\bar{x})^{2}} \]

If you were handed a distribution and you were asked to measure a characteristic “fatness” for the distribution, your estimate would be approximately \(\sigma\). Note that \(\sigma\) has the same units as the original data, so if your data were in meters, \(\sigma\) would also be in meters.

1.9 Quick intro to the Gaussian distribution

We won’t get to Normal (a.k.a. Gaussian) distributions properly until Week 3, but we will need one fact about the “Standard Normal Distribution” now. The Standard Normal distribution is a Normal (or Gaussian, bell-shaped) distribution with mean equal to zero and standard deviation equal to 1. 68\(\%\) of the probability is contained within 1 standard deviation of the mean (so from -\(\sigma\) to +\(\sigma\)), and 95\(\%\) of the probability is contained within 2 standard deviations of the mean (so from -2\(\sigma\) to +2\(\sigma\)). (Actually, 95\(\%\) is contained with 1.96 standard deviations, so sometimes we will use the more precise 1.96 and sometimes you will see this rounded to 2.)

1.10 Overview of Univariate Distributions

Discrete Distributions

Binomial

Multinomial

Poisson

Geometric

Continuous Distributions

Normal/Gaussian

Beta

Gamma

Student’s t

\(\chi^2\)

1.11 What can you ask of a distribution?

- Probability Density Function: \(P(x_1<X<x_2)\) (continuous distributions)

Stop: Let’s pause for a second and discuss the probability density function. This is a concept that student’s often struggle with. What is the interpretation of \(P(x)\)? What is \(P(x=3)\)? Can \(P(x)\) ever be negative? [No.] Can \(P(x)\) ever be greater than 1? [Yes! Why?]

Probability Mass Function: \(P(X=x_1)\) (discrete distributions)

Cumulative Density Function (CDF): What is \(P(X \le X^*)\)?

Quantiles of the distributions: What is \(X^{*}\) if \(P(X \le X^{*})=0.37\)?

Sample from the distribution: With a large enough sample, the histogram will come very close to the underlying PDF.

Note that the CDF is the integration of the PDF, and the PDF is the derivative of the CDF, so if you have one of these you can always get the other. Likewise, you can always get from the quantiles to the CDF (and then to the PDF). These three things are all equally informative about the shape of the distribution.

1.11.1 Expected Value of a Random Variable

In probability theory the expected value of a random variable is the weighted average of all possible values that this random variable can take on. The weights used in computing this average correspond to the probabilities in case of a discrete random variable, or densities in case of continious random variable.

1.11.2 Discrete Case

\[ X = \{X_1, X_2,...,X_k\} \\ E[X] = \sum_{i=1}^n{X_i \cdot P(X_i)}\]

- Example: Draw numbered balls with numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 with probabilities 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.6.

\[ \begin{align*} E[X] &= (0.1 \cdot 1) + (0.1 \cdot 2) + (0.1 \cdot 3) + (0.1 \cdot 4) + (0.6 \cdot 5) \\ &=4 \end{align*}\]

1.12 A brief introduction to inference, logic, and reasoning

INDUCTIVE reasoning:

A set of specific observations \(\rightarrow\) A general principle

Example: I observe a number of elephants and they were all gray. Therefore, all elephants are gray.

DEDUCTIVE reasoning:

A general principle \(\rightarrow\) A set of predictions or explanations

Example: All elephants are gray. Therefore, I predict that this new (as yet undiscovered) species of elephant will be gray.

QUESTION: If this new species of elephant is green, what does this do to our hypothesis that all elephants are gray?

Some terminology:

Null Hypothesis: A statement encapsulating “no effect”

Alternative Hypothesis: A statement encapsulating “an effect””

Fisher: Null hypothesis only

Neyman and Pearson: H0 and H1, Weigh risk of of false positive against the false negative

We use a hyprid approach

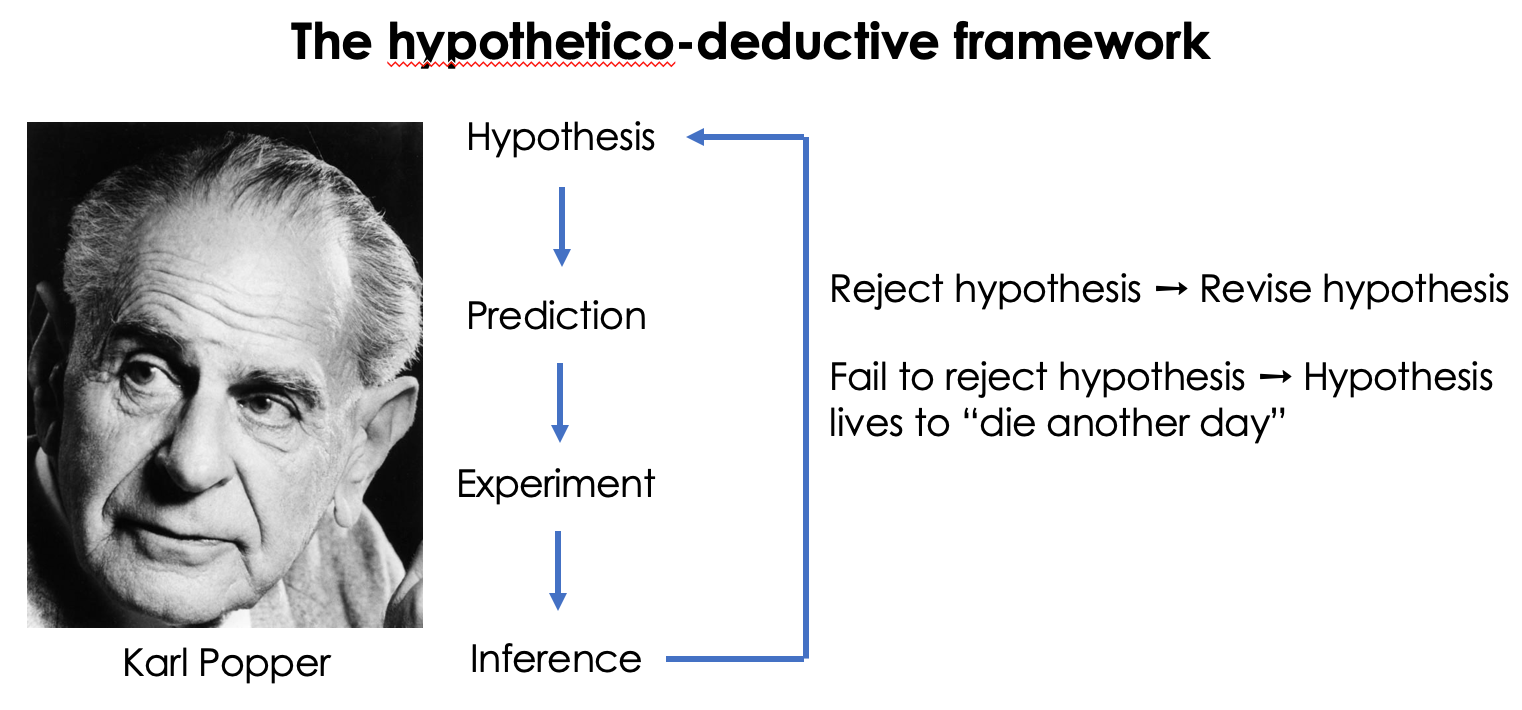

Figure 1.4: Hypothetico-deductive view of the scientific method. Photo Source: LSE Library

Not all hypotheses are created equal. Consider the following two hypotheses:

H\(_{1}\): There are vultures in the local park

H\(_{2}\): There are no vultures in the local park

Which of these two ways of framing the null hypothesis can be rejected by data?

Hypothesis can only be rejected, they can never be accepted!

“Based on the data obtained, we reject the null hypothesis that…”

or

“Based on the data obained, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that…”

More terminology

Population: Entire collection of individuals a researcher is interested in.

Model: Mathematical description of the quantity of interest. It combines a general description (functional form) with parameters (population parameters) that take specific values.

Population paramater: Some measure of a population (mean, standard deviation, range, etc.). Because populations are typically very large this quantity is unknown (and usually unknowable).

Sample: A subset of the population selected for the purposes of making inference for the popualtion.

Sample Statistic: Some measure of this sample that is used to infer the true value of the associated populatipn parameter.

An example:

Population: Fish density in a lake

Sample: You do 30 net tows and count all the fish in each tow

Model: \(Y_i \sim Binom(p,N)\)

The basic outline of statistical inference

sample(data) \(\rightarrow\) sample statistics \(\rightarrow\) ESTIMATOR \(\rightarrow\) population parameter \(\rightarrow\) underlying distribution

Estimators are imperfect tools

Bias: The expected value \(\neq\) population parameter

Not consistent: As \(n \to \infty\) sample statistic \(\neq\) population parameter

Variance